HPF Firenza

About these cars and why I like them

About these cars and why I like them

The car was launched in 1973 at the Geneva motor show, and at that time its styling was certainly unusual, and very bold for a Vauxhall. From a modern perspective it's hard to see what the fuss might have been about, since all cars since then have tended to look somewhat like it. That's not surprising when you consider that the styling of the HPF was also functional - it lowered the aerodynamic drag of the car significantly compared to the flat-fronted Magnums and Vivas on which it was based. The drag reduction is equivalent to having an extra 30bhp at your disposal above 100mph. There's no doubt that the styling looks American, and when you consider that this was one of GM designer Wayne Cherry's first passenger car designs for Vauxhall, it's perhaps no surprise. The same styling cues also found their way into the (later) Pontiac Trans-Am and Camaro models, so it seems as if GM wanted to try out the droopsnoot concept across all of its mid-to-late 70s models worldwide. Vauxhall's subsequent Chevette, Cavalier and Carlton models further developed the look in the UK.

The Good

Because the Firenza was originally a more traditional design, the droopsnoot version was basically an exercise in building a bolt-on body kit, in an age where such things were more or less unheard of. The clever one-piece nosecone is, in my view, remarkable for the fact that it doesn't look like the bolt-on fibreglass afterthought that it really is - it works with the existing lines of the flat-fronted car to create something that works from almost any angle you look at it. Even the unusual but wholly unmodified humped and fluted bonnet - a Vauxhall tradition - with its pointy bit sticking forward at the front works into the nosecone supremely elegantly.

And by the way - those headlamp covers? They're toughened glass (not perspex as commonly assumed) and they curve in two directions! Not an easy thing to design or make, back then.

Apart from the body, the HPF has other interesting features unique to this car. Its engine was an uprated version of the chunky 2.3 litre "slant four", with larger, higher-lift valves, a tubular exhaust manifold and twin 175 CD Stromberg carburettors. A 5-speed dog-leg ZF transmission drove an uprated rear axle assembly built from Ventora and Cresta bits. All of this elevated performance to respectable levels - not Porsche beating, but certainly very good for a car of its class: 8.5 second 0-60, and 120mph top end. The brakes were taken from the 3.3 Ventora, and the suspension was stiffened and lowered compared with the Magnum. Handling was considered very good - certainly far better than the cart-horse sprung Fords of the day, something that Vauxhalls had long had the advantage in, having widely adopted coil springs and double-wishbone suspension across the range of models in the 60s. Interior wasn't all that different from a top-end Magnum, featuring the 7-dial instrument cluster, grey-panelled cloth seats an a 2+2 configuration. The headlining was black rather than white, giving the car a rather sombre feel inside. Indeed the carpet, door panels - everything was black. The glovebox was deleted in favour of a "passenger grab handle". I've never been sure what the idea here was - certainly making the passenger feel secure wasn't the usual result. As a unique interior feature, it was also a rather poorly made and badly fitting item.

The Bad

The nose cone wasn't the only thing - some of the steps taken to turn a standard Firenza shell into an HPF one were far from pretty. The hole in the transmission tunnel that admitted the gear level was in the wrong position for the ZF 'box, so Vauxhall's solution was to take a flame-axe to it and make it bigger! The gear-level gaiter was fixed to a piece of folded painted metal inside to hide the ugly gash in the carpet and floor. I can only assume that this was thought up at ten to five on the Friday afternoon prior to production starting, as it's a thoroughly nasty and unprofessional hack. (Note - it seems this varies from car to car, with different solutions tried during production - so maybe mine was just an especially bad one). It was a similar story with the cutouts in the radiator brackets needed to clear the much wider Cibié headlamp clusters. The front wings were cut back where they mated to the nosecone, but here Vauxhall did a decent job and the result looks good.

The ZF 'box is a tight fit in the tunnel - not a problem for production but an absolute pig to get in and out of the car for servicing. And that 'box - ooh, it's noisy. Strong, but noisy. Whiny synchros, rattly bearings, and poor interior insulation - indeed, Jeremy Clarkson's comment - "sounds like a sporting tractor and goes about as well" does have some basis in fact. Still, it does go pretty well, and is a nice handling car. If you can put up with all the transmission noise it's rewarding to drive. Bags of torque, and unbreakable with it. The engine does tend to run hot though, partly thanks to the tubular exhaust in a confined space. Vapour-lock on hot days can be a problem. Pinking can be hard to eliminate, especially now that you don't get lead in petrol - that car was built for VLP - very leaded petrol.

The Ugly?

The HPF's looks are not universally admired; it seems to be one of those love-it-or-hate-it jobs. But I like it, and to this day it holds up as a good looking car in my book. Because it became the prototype for the rest of Vauxhall's 70s models, it looked modern alongside them in exactly the same way that the Viva didn't. The benefits of the droopsnoot aerodynamics were obvious to everyone, and soon everyone was in on it. Ford's 1976 RS2000 copied the droopsnoot shamelessly, and when Ford's replacement for the venerable Cortina, the Sierra, debuted in 1982, its front end was remarkably droopsnoot-like. Every car built since that time has gone much the same way - flat fronts are unusual today. Put an HPF in a lineup with cars that are 20 years newer and it doesn't look out of place. So much so that my own HPF, with its 1974 registration plate got mistaken for an unidentified 1990 'G' registered car at one of its MOT tests (and initially failed because it fell short of the modern emissions requirements by 0.1%CO).

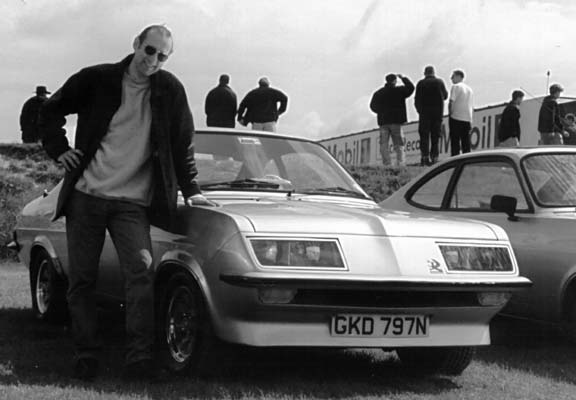

Sadly I no longer own one of these cars. I sold my HPF GKD797N (one of the most well-known ones on the 'net since I contributed a photo of it to Wikipedia) when I emigrated to Australia in 2002. I regret that, especially as I sold it at a lower price than I should have due to pressure of time. I don't think that car has been seen since at group meetings, which is a pity. I'd like to get another, but they are hard to find in good condition and those that do exist are by and large highly cherished. So I'm not holding my breath. Still, if you have a nice one and want to sell, think of me!

My Car: GKD797N

GKD797N was the second HPF I've owned. The first (RGJ904P) I bought in 1985. It was owned by a local publican, and was highly souped up, with a Blydenstein job on its engine so it put out nearly 200bhp. One night he turned it over, and the car was written off. I think it's fair to say that due to the level of blood in his alcohol stream he didn't want to make a big fuss about it, so I managed to acquire it from the insurers for just 300 quid. A bargain just for the engine alone. Unfortunately the car needed reshelling since the roof was badly crushed. There were also other problems such as a holed radiator and a bent half-shaft. Fixing the half shaft brought me into contact with the Droop Snoot Group for the first time, and the car was briefly made to run again, accident damage and all. It was obvious just what a total road burner it was - an animal of a car. Unfortunately my resources and expertise at the time didn't stretch to reshelling it, so I reluctantly sold it on, for a lot more than I'd paid for it.

After that I didn't think about HPFs much, but around 1995, I decided to go to the NEC Classic Car show, since at that time I lived in the area. The Droop Snoot Group was the first stand I saw on entering, and that brought it all back. "I used to have one of those!" I exclaimed as I saw the HPF on display. "Oh no, not another one" groaned the guy on the stand (who turned out to be DSG stalwart Terry Cobbold). We got chatting and my interest in the car was reawakened. I joined the club, and started to get involved, reading their club mag and finding out as much as I could about the cars. I started looking for a good HPF around then. It took more than a year, but finally, I saw GKD for sale in the then-new "Retro" magazine (now called "Classics"). I had to have her and drove up to Mablethorpe in Lincolnshire to do the deal. The car had been previously cherished by a Scottish owner, who had spent a great deal of time and money on its continued preservation. I forget the story of how it happened to end up in Mablethorpe - something to do with a part-exchange deal. Anyhoo, the car was bodily extremely sound (incredibly, it had been wax injected from new, giving it a good deal of rust protection that the factory hadn't thought to bother with), though the mechanicals were somewhat stale and rough. I bought it, of course.

Over the next several years I lavished much attention on making it run as well as it looked. Total transmission rebuild from flywheel to rear drums, new suspension bushes everywhere. Brand-new stainless steel exhaust system. Refurbished wheels, and brand new Yokohama 205HR13 A509 radials. The tyres on the car were perished1970s originals - with all the grip that implied. The Firenza benefits greatly from modern tyre technology and going up from its original 185 to a softer 205 improves grip tremendously. There's plenty of room under the standard arches too. It never became refined exactly, but heaps better than the day I collected it. I think the previous owner hadn't really driven it, whereas I certainly did. I took it to meetings up and down the country, and once it was in fine running order, started doing the odd track day in it. While I was always very conscious of its essential unreplaceability and never gave it 100%, I did have fun! Finally the car was mechanically sorted, and the final gift to it was a complete upholstery restoration. Unfortunately the original material was unavailable, but in any case was not very hard wearing - so my car had very high-quality grey Audi seat material fitted to the original seats and to the original pattern - a big improvement in my view. The well-worn carpet was also replaced.

Fame of sorts

In 1999, the classic car press started to take a bit more than their usual interest (i.e: none) in the marque, mostly due to the diligence and persistence of the DSG's publicity secretary, Terry Price. '99 was the 25th anniversary of the Thruxton launch of the car, and the DSG was determined to recreate the event as well as have a jolly good club meeting to celebrate. So in the run-up to that, I got invited to do two magazine features on the HPF. The first was for Classic Cars , but was fairly low-key. A photographer came round to my place and shot the car against a white backdrop for the static shots, and then had me endlessly circle a roundabout for thirty minutes for the rest. Still, it was a good article feature. The second shoot was much more exciting. This time Retro/Classics wanted to do a re-run of a 1974 run-off between the HPF, the RS2000 Escort and the Triumph Dolomite Sprint. At Thruxton. So after three nanoseconds thought, I agreed to take part! The shoot was fun, and the resulting article spectacular, with the Firenza getting top billing, the cover picture, and coming out on top in the three-car "test". It was something of a fix, in the sense that Classics wanted to highlight the forthcoming DSG Thruxton event and showcase a car that was not the usual one for a classics magazine. So the result of the "test" was something of a foregone conclusion, but nevertheless it was fun to "compete" against the other two - both of which were stunning examples of their kind. There's no doubt that on the day, my car attracted all the attention - after all, everyone sees Escorts and Triumphs any day of the week. The magazine said "The Firenza has a presence that overshadows the [other two]". That's definitely how it felt on the day, and everyone knew it.

The End

Eventually I found that I wasn't getting enough use out of the car, and it sat for long stretches of time in a lock-up garage. I still used it a few times a year, but increasingly found less time available. With the impending move to Oz coming up, I decided to sell. A buyer was readily found - these cars don't hang around for long. The day I sold it, it had been laid up in the lock-up for probably about six months over the winter. One problem - condensation in the clutch had managed to bond the whole lot solidly together. Try as I might (and boy, did we give it hell to try and break that stuck clutch open!) it was stuck fast. This didn't deter the buyer, who was prepared to pull the 'box out and fix it. So my last sight of the car was being towed away by an RAC Rescue truck - very sad. I only hope that the car is still as cherished as it has always been, and is back on the road, giving its owner the same pleasure it gave me. Or if not - well, I'll take her back!

Firenza futures?

If the HPF had been a bigger success, 1976 would have brought fuel injection to the model - Roy Cooke's notes presented to the DSG prove this. In my view that would have been an excellent move - the carburettors are problematic on this car. A common upgrade is the fitting of twin 40 DCOE Webers, but that of course does little for the thirst. Beyond that, at the time there were many Blydenstein-derived mods for tuning the engine, many of which can still be dug up on eBay, etc. 180+ bhp is not difficult to achieve, and the car will always benefit from more power. Trouble is, that slant-four is a bit of a dog by modern standards. Big pistons make it unrefined and "lumpy", and not very free-revving. Yes it's immensely strong and torquey for its size, but let's face it, it's old tech. I've often daydreamed about putting a modern fuel-injected V6 into an HPF. It would be more or less a drop-in job, there's plenty of room. Something like a 3.2 litre Holden would fit the bill nicely. Purists will be spluttering, but it's possibly where the model might have gone anyway, had it lasted into the 80s, like the Capri. Combined with modern standards of interior sound insulation, such a car could be stunning. Maybe one day...

Other Firenza resources on the web:

Droop Snoot Group website (finally updated after years of neglect - looks great guys! well done).

The Wikipedia entry (which I wrote, mostly)

Vauxhall Heritage article by Tony Shaw

Scans of the original 1973 sales brochure

Mike Edwards' personal site (may not work well in Safari/Firefox/Opera, etc - I can never see the images)

Bromfield Hall - Thruxton HP owner's personal site.

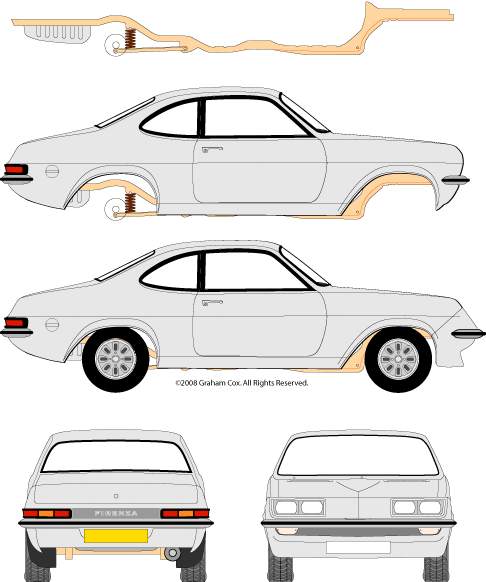

Update, January 2008: I have made a vector profile image of the HPF and Magnum coupé which I believe to be reasonably accurate (though more work is needed to obtain accurate profiles of the exterior cross sections of the shell. You can download a copy of this in PDF format here (smaller preview image shown below). The PDF image can be rendered at any desired scale without loss of quality. The image has been derived from dimensional data from the Vauxhall Technical Supplement with additional photographic input. 1.2MB download.

© 2006-2008 Graham Cox